Background Information

GHG Reduction

- Greenhouse Gases and Climate Change

- The Canadian Context

- The Role of the Health Care Sector

- Benefits of GHG Emission Reduction

Water Conservation

Project Directory

1. Greenhouse Gas and Water Toolkit

2. Climate Change Resiliency Mentoring

3. Health Care Facility Resiliency Toolkit

Greenhouse Gases and Climate Change

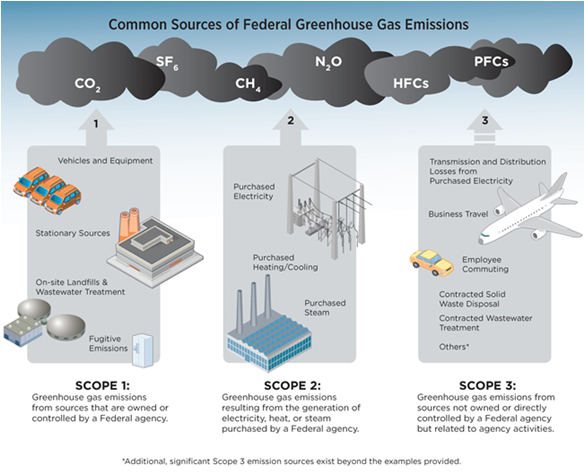

Gases that trap heat in the atmosphere are often called greenhouse gases. Climate change is considered one of the most important environmental issues of our time since it will affect all of these aspects of our natural environment. Although climate change can be caused by both natural processes and human activities, scientific studies have shown that recent warming can be largely attributed to human activity, primarily the release of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.[1]

Climate change represents a serious risk to human health in the coming decades. A November 2014 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated with high confidence that "Health impacts [of climate change] include greater likelihood of injury and death due to more intense heat waves and fires, increased risks from foodborne and waterborne diseases, and loss of work capacity and reduced labour productivity in vulnerable populations... Globally, the magnitude and severity of negative impacts will increasingly outweigh positive impacts."[3]

GHG emissions in Canada are driven by a number of factors, such as economic and population growth as well as the mix of energy supply. Emissions in Canada's commercial and residential buildings increased by 14 Mt between 1990 and 2005, and then remained relatively stable around the 2005 levels through to 2011. Since 1990 buildings have accounted for about 12% of Canada's GHG emissions in any given year. The stability in emissions since 2005 is attributed mainly to energy retrofits, as 40% of the floor space has seen some level of energy retrofit between 2005-2009.[5]

Because the public health and environmental impacts of climate change are becoming more clear daily, there is a growing call to measure, track, and reduce organisations' greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, health care facilities in Canada are vulnerable to climate change. Climate-related hazards are expected to create risks that can disrupt health care facility services and delivery.[7]

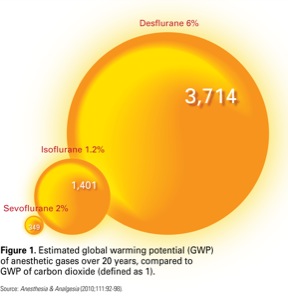

Most of the GHG emissions for which health care is responsible are the result of building energy use, and the indirect effects of procurement and waste management. The unregulated direct release of volatile anesthetic gases - known in health care as waste anesthetic gases or WAGs - are an emission unique to health care. The most widely used potent inhaled agents (sevoflurane, desflurane and isoflurane, and nitrous oxide,) undergo very little in vivo metabolism in clinical use. They are exhaled and then scavenged by anesthesia machines with little or no additional degradation, and are typically vented directly into the atmosphere along with medical gases. The human body metabolizes less than 5% of the anesthesia gas during a procedure, with the remaining 95% exhausted to the outdoor environment.[8]

Reducing GHG emissions can benefit health care organisations with respect to their resiliency, environmental stewardship, and community leadership, as well as offering potential financial benefits. In some provinces, GHG reduction is already an important aspect of compliance with government regulations. In November 2007, British Columbia enacted legislation to establish provincial goals for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Under the Greenhouse Gas Reductions Targets Act (GGRTA), the B.C. public sector must be carbon neutral in its operations for 2010 and every year thereafter.[9] In Ontario, hospitals are required to report on their GHG emissions under the Green Energy Act.[10] Similar requirements may be put in place nationally in the future.

Water Use in Canada

Canada is widely seen as a nation rich in water resources, accounting for 8% of the world's renewable freshwater resources. A comparison of total annual water renewal rates vs. total annual demand puts Canada in the top tier of countries whose gross renewable supplies far exceed its water-use demands. The perception of abundance masks other realities concerning the availability of these resources and discounts the significance of the mounting list of situations where sustainable-use concerns exist at the local and regional levels.[1]

Hospitals are often the largest water users in a community. Inefficient and non-productive uses of water continue to drive avoidable expenditures and debt accumulation for the construction, expansion, operation and rehabilitation of municipal and private water infrastructure. They also result in excessive energy consumption and contribute to the inefficient use of other resources.[2]

Much of Canada's water wealth is situated in areas far removed from the point of need thereby limiting its availability and potential for development. The cumulative demand for water results in competition for locally available supplies and threatens aquatic ecosystems and environmental health. Climate change predictions show that many parts of the country are likely to experience increasing risks from reduced water availability and increased water demand.[3]

Clean water is intimately connected with human health. Processing potable water is energy intensive and thus contributes to greenhouse gases associated with energy generation (for the treatment, pumping, and maintenance of the potable water systems). In some municipalities, water treatment systems represent the highest energy demand over all other municipally-controlled energy use categories. In addition, potable water processing often includes the use of toxic disinfection chemicals such as chlorine.[4]

Only about 20% of water used in urban areas is used for drinking and sanitary purposes, while the other 80% does not require treatment to potable standards. As significant consumers of potable water, health care facilities can spur the market to conserve potable water and to start depending on non-potable water sources for process uses.[5]

Canadians consume more water per capita than almost any other developed nation.[6] High consumption rates of potable water places stress on lakes, aquifers, and waterways and can alter an entire ecosystem's functioning.[7]

The discharge of polluted water into these waterways can also seriously disrupt aquatic ecosystems. Sewage and wastewater effluent can pollute local ecologies through non-point sources (e.g., use of fertilizer and pesticides in landscaping), sanitary sewer overflows, and stormwater sewer overflows.

Some water conservation strategies may increase first cost. However, these measures have the potential to reduce a facility’s operational or life cycle costs as well as enhance relations with the surrounding community. A hospital that does not burden the local utilities demonstrates environmental and community stewardship, and is viewed as a desired neighbor. These funds can be reinvested into further conservation strategies or diverted to upgrade equipment or hire staff, a health care institution’s largest annual expenditure.[8]

Infection control concerns and potential contamination of potable water supplies pose the strongest challenges to domestic water conservation in hospitals, leading to regulations such as prohibiting piped, non-potable water systems.[9]

In addition, some conservation technologies, such as sensor controls for faucets and flush valves, have higher first costs (though are often favorable relative to life cycle costs) and may require an aggressive education campaign to address infection control and time management concerns with facility managers, regulators, and other concerned parties.[10]